Each year, hundreds of climbers set their sights on Mount Everest, hoping to reach the highest point on Earth. For many, it’s the ultimate bucket list goal, a once-in-a-lifetime dream. But not everyone returns from the mountain. Tragically, over 300 climbers have lost their lives on Everest, and many of them still remain there today.

Dead bodies on Mount Everest are more than just frozen statistics they are real people, each with a story, a family, and a dream. Some are barely visible under layers of snow, while others are eerily preserved, their colorful gear still intact. Many lie just beside the climbing route, quietly reminding every climber of what’s at stake. Yet, despite all the danger and loss, more climbers arrive every season, chasing that same summit dream.

But why are so many of these bodies still on the mountain? Why aren’t they brought down and laid to rest properly? The truth is, recovering a body from Everest’s death zone is one of the most dangerous missions in mountaineering. The risks are high, the terrain is brutal, and the costs, both human and financial, are often too significant to bear.

In this article, we’ll explore the haunting reality of dead bodies on Mount Everest, the reasons they remain untouched, and the stories behind some of the most well-known climbers who never made it back. From extreme weather to ethical dilemmas, we’ll take you deep into the mountain’s dark side, where nature is unforgiving, and every step could be your last.

Why Are Dead Bodies on Mount Everest So Difficult to Recover?

Bringing down bodies from Mount Everest is one of the most dangerous and demanding tasks in high-altitude mountaineering. It’s not just about manpower—it’s about battling nature at its most extreme. Many have tried and failed. Even attempts at body recovery can result in more lives lost.

Thin Air, Thick Risks

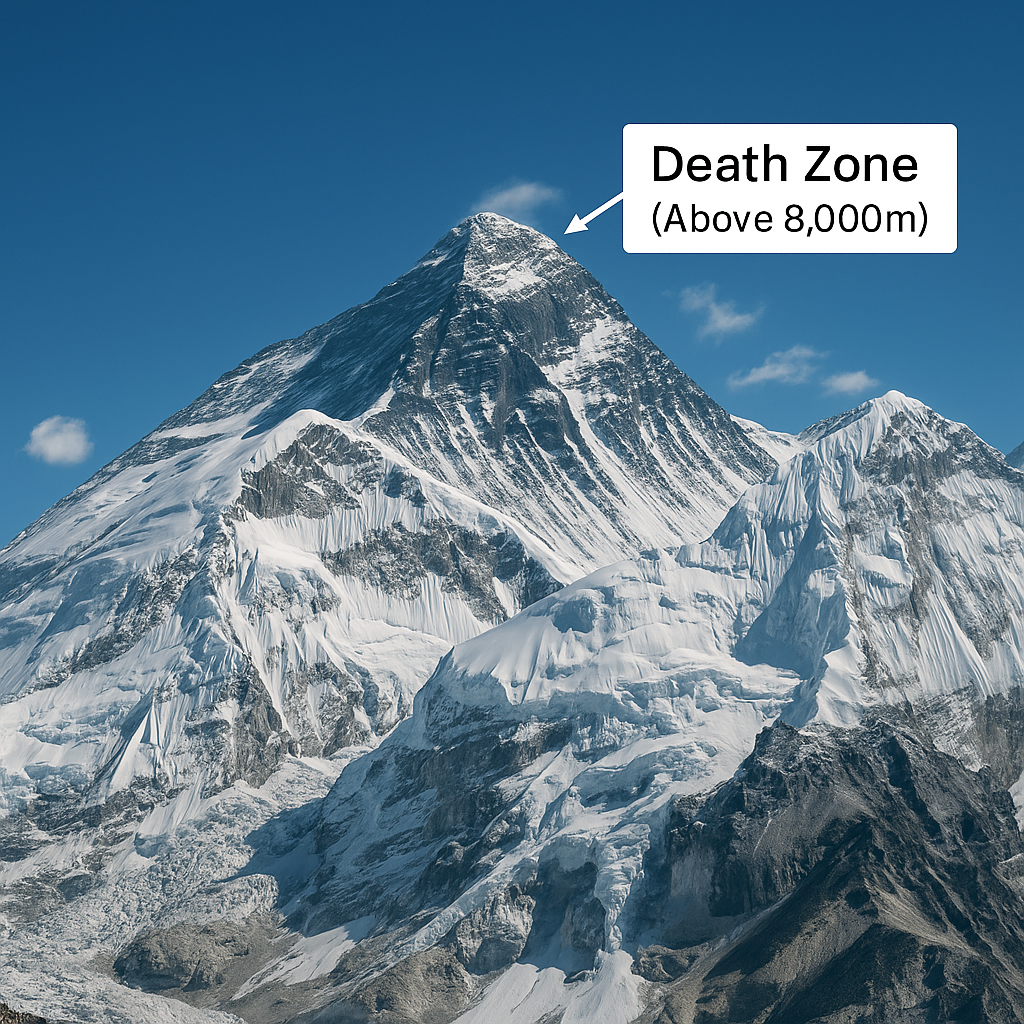

- The Everest death zone begins above 8,000 meters, where oxygen levels drop to approximately 30% of those found at sea level. At this point, the human body is slowly dying, even while at rest.

- Every action from walking to breathing becomes painfully difficult. Adding the task of carrying a frozen body that weighs over 80 kg (often more due to the presence of ice) makes it nearly impossible.

- Even for highly trained Sherpa guides or elite climbers, the risks of hauling a dead body down are immense. Climbers can experience sudden altitude sickness, fall into crevasses, or simply collapse from exhaustion.

The route to the summit isn’t smooth. It’s a jagged, icy path lined with ladders, ropes, and deadly drop-offs. Trying to lower a lifeless body through those sections requires a coordinated team, specialized equipment, and perfect weather conditions. One misstep could result in another tragedy.

Freezing Temperatures Preserve the Dead

- The sub-zero temperatures at high altitude freeze bodies within hours, turning them stiff and almost impossible to move.

- Over time, they become frozen to the terrain itself. Some bodies are cemented into the ice, requiring hours of dangerous chipping and pulling to dislodge.

- Bodies remain visually intact for decades, sometimes eerily so. Climbers have described seeing faces, clothes, and even open eyes still visible through ice.

This preservation adds another layer of psychological difficulty. For rescuers, it’s not just a physical job it’s also emotionally draining. You are not just handling a corpse, but someone’s family member, friend, or hero, frozen in place like a statue. Climbers have often had to step over these bodies on their way to the summit, knowing they could meet the same fate.

Logistical and Ethical Challenges

- Recovering a body from the mountain requires a whole team, often comprising 6–10 people, all of whom are acclimatized and trained for high-altitude operations. Organizing this kind of effort is time-consuming and expensive.

- It’s not just about bringing the body down; it’s also about ensuring that no additional lives are lost in the process. Rescue helicopters cannot fly that high, so all recovery must be done by foot or by rope.

- There’s also a moral dilemma. Some climbers express the wish to be left on the mountain if they die. Their families honor those wishes, turning Everest into both a grave and a memorial.

Climbers, Sherpas, and expedition leaders must carefully weigh their options. In most cases, they choose not to risk more lives for a recovery. That decision isn’t made lightly, and it’s often accompanied by grief and guilt. But on Everest, safety always comes first. The mountain has already claimed too many.

Who Are Some of the Most Famous Dead Bodies on Mount Everest?

Mount Everest is not only known for breathtaking views and legendary climbs it’s also home to some of the world’s most haunting reminders of ambition and mortality. Among the hundreds of deceased climbers on Everest, a few stand out—not because their lives were more important, but because their stories became symbols of the risks involved in chasing the summit.

These bodies became frozen milestones on the way up, often passed by those still alive, trying to achieve what these climbers could not. Their stories are both cautionary and unforgettable.

Green Boots – A Tragic Trail Marker

- “Green Boots” is the nickname given to the body believed to be Tsewang Paljor, a member of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police who died during the 1996 Everest disaster on the northeast ridge.

- He died along with two other teammates in a snowstorm, and his body became a landmark along a small rock cave just below the summit.

- His neon green climbing boots were so distinct that every climber passing the spot for nearly two decades instantly recognized him.

What made Green Boots iconic wasn’t just his gear—it was the location of his death. His body lay curled in a fetal position just off the trail, acting as a grim checkpoint for every climber on the northern route. For years, climbers rested near him, took shelter in the same cave, or photographed the eerie sight without fully knowing his name. Only later did reports confirm his likely identity as Paljor, who died tragically young while serving his country.

Despite brief efforts to move his body out of public view in recent years, his image and story continue to circulate widely, and he remains one of the most recognizable figures on Mount Everest.

Sleeping Beauty – Francys Arsentiev

- Francys Arsentiev was the first American woman to reach the summit of Everest without the use of supplemental oxygen in 1998.

- Tragically, the victory was short-lived. On the descent, she became severely weak, disoriented, and unable to continue. Her husband, Sergei Arsentiev, tried to rescue her but also went missing and later died.

- She became known as “Sleeping Beauty” because of the peaceful, almost serene position in which she was found, seated and leaning on her side, her face pale and exposed.

Her death shook the mountaineering community. Several climbers passed her on their way to the summit, offering limited help but unable to rescue her due to exhaustion and thin air. Her final words, whispered to one climber, were “Don’t leave me.” But on Everest, staying behind could mean death for both.

Her body remained on the mountain for nearly a decade before a private expedition finally moved it out of sight as a tribute to her bravery. Still, her legacy lives on—not just as the first American woman to climb Everest without oxygen, but as a painful reminder of the decisions climbers must face when rescue is almost impossible.

George Mallory and Sandy Irvine – The Lost Legends

- George Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine were British mountaineers who attempted to summit Everest in 1924—nearly three decades before Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay officially made it.

- They disappeared high on the northeast ridge. Mallory’s body was discovered in 1999 at around 8,200 meters, still wearing his tweed clothing and carrying an altimeter.

- Irvine’s body has never been found, and neither has the camera they were carrying, potentially holding the answer to the greatest Everest mystery: Did they reach the summit before dying?

Mallory’s famous quote, “Because it’s there,” has become symbolic of the mountaineering spirit. When his body was found 75 years later, he was face-down in the rocks, with broken ribs and a rope injury around his waist—evidence of a fall while roped to Irvine.

The camera that could rewrite history is still missing, likely still somewhere near the summit. If found, it might prove that Mallory and Irvine were the first to stand on the world’s highest peak. Until then, their story remains half-written, suspended between legend and fact.

Their tale is distinct from other Everest accounts because it reflects the earliest era of high-altitude climbing, conducted without oxygen, radios, or modern gear. They were pioneers, possibly the first to touch the top, and certainly among the first to pay the ultimate price.

What Is the Death Zone, and Why Is It So Deadly?

The “death zone” is one of the most feared terms in high-altitude climbing—and for good reason. It refers to the part of Mount Everest (and other tall mountains) where life is no longer sustainable for long periods. Above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet), every breath, every movement, every heartbeat becomes a struggle.

Even for the fittest climbers with years of preparation, the death zone can quickly turn a dream into a disaster.

Oxygen Levels That Can Kill

- At sea level, the air contains about 21% oxygen, which our bodies readily absorb. But in the death zone, oxygen drops to just 30–35% of what we’re used to.

- Breathing becomes shallow and inefficient, even with rest. Without supplemental oxygen, most people can’t last more than a few hours at this altitude.

- The body starts to deteriorate. Muscles weaken, digestion slows, judgment becomes impaired, and the brain struggles to function clearly.

Climbers often describe the death zone as walking in slow motion while drowning. Every step toward the summit takes several minutes, with multiple breaks just to catch your breath. Talking becomes hard. Even tying a bootlace can leave you gasping for breath.

Supplemental oxygen helps, but it’s not a guarantee. Many climbers have died despite carrying extra tanks—either they ran out, equipment failed, or they miscalculated their needs.

Life-Threatening Medical Conditions

- High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE): A condition where the brain swells due to lack of oxygen. Symptoms include confusion, hallucinations, dizziness, and loss of coordination. If untreated, it leads to coma and death, sometimes within hours.

- High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE): Fluid builds up in the lungs, causing severe shortness of breath, coughing, and a feeling of suffocation. Even mild cases can become fatal if a climber doesn’t descend quickly.

- Hypothermia and frostbite: With temperatures often below-30°C and powerful winds, any exposed skin can freeze in minutes. Loss of limbs is common, and death can occur quietly in sleep.

These conditions can hit suddenly, even after proper acclimatization. Climbers have been known to collapse mid-step or begin speaking incoherently just minutes after showing no symptoms.

One of the most harrowing aspects? There’s no hospital up there. No real rescue team can reach you fast enough. And no helicopter can fly safely in such thin air.

Decision Fatigue and Physical Exhaustion

- By the time climbers reach the death zone, most have already spent weeks acclimatizing and days climbing. They’re dehydrated, sleep-deprived, and mentally drained.

- The higher they go, the more they experience decision fatigue—a dangerous phenomenon where the brain’s ability to make sound choices declines.

- In this weakened state, climbers must decide whether to continue to the summit, turn back, wait, or descend. The wrong choice can—and often does—lead to death.

One example is David Sharp, a British mountaineer who died in the death zone in 2006. Over 30 climbers passed him as he lay dying near a rock alcove, many assuming he was already dead or beyond help. Some were too tired to act. Others feared for their own survival.

Stories like these show how thin the margin is between pushing forward and perishing. The summit may be only a few hundred meters away, but it could take hours to reach, and just one bad decision can seal your fate.

Why Do Climbers Still Attempt Mount Everest Despite the Risks?

Mount Everest stands as a symbol of ambition, danger, and glory. With hundreds of lives lost and so many dead bodies on Mount Everest, one might wonder—why do people continue to risk everything for the summit?

The answer is a mix of personal drive, global recognition, spiritual challenge, and the dream of conquering the world’s highest peak. For some, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime goal. For others, it’s a calling they cannot ignore.

For those seeking high-altitude challenges with fewer crowds and more cultural immersion, alternatives like the Manaslu Circuit Trekking route in Nepal offer raw, remote adventure, without the commercial overload of Everest.

The Prestige of Scaling Mount Everest

- Mount Everest is part of the prestigious Seven Summits, making it one of the most sought-after achievements in mountaineering.

- Reaching the summit gives climbers a permanent place in a global fraternity—those few who stood on top of the world.

- It’s about legacy. For many, summiting Everest is the pinnacle of a lifetime of training, discipline, and sacrifice.

There’s a sense of immortality tied to scaling Mount Everest. To write your name into the history of Everest climbs is to be remembered, no matter what line of work you come from. This prestige draws corporate leaders, athletes, soldiers, doctors, and everyday dreamers from all over the world.

People ask, “Why climb Mount Everest?” The most common answer remains Mallory’s: “Because it’s there.” But beneath that, it’s also because it’s one of the few places where your limits are truly tested—and your victory is undisputed.

Commercial Expeditions and Crowded Routes

- Today’s Everest expeditions are not the exclusive territory of elite mountaineers. Commercial companies have opened the mountain to amateurs with enough money and moderate fitness.

- Guided tours now handle permits, route planning, equipment, and even Sherpa support, making the climb seem achievable to more people than ever before.

- However, this accessibility has led to severe overcrowding. During peak Everest season, climbers often get stuck in long queues near Camp IV and the South Summit.

In 2019, a photo of a human traffic jam just below the summit went viral. Dozens of climbers stood shoulder-to-shoulder in the death zone, waiting their turn to reach the top. Several people died that day, not due to falls or avalanches, but because they waited too long in thin air.

While commercial expeditions make dreams possible, they also contribute to bottlenecks and increased fatalities. The mountain is now busier than ever, and the competition to reach the top is fierce, even when it’s life-threatening.

The Role of Social Media and FOMO

- In today’s digital world, Everest summits are shared instantly. A climber can reach the top in the morning and post a selfie by evening.

- This instant recognition fuels a wave of climbers who want their moment on the world’s highest peak, not just for the experience, but for the likes, follows, and legacy.

- Social media has turned Everest into more than a climb—it’s now a stage.

This “Fear of Missing Out” (FOMO) pushes some climbers beyond their skill level. They chase the summit not because they’re ready, but because they want to keep up with others. Tragically, that has resulted in avoidable deaths. Some die climbing Mount Everest because they overestimate their capabilities, underestimate the mountain, or cannot walk away from the summit fever.

There’s also peer pressure. Many climbers invest tens of thousands of dollars into training, gear, and permits. Walking away feels like failure. The pressure to submit can override logic, even as their oxygen runs out or storms roll in.

What Happens After a Climber Dies on Everest?

When someone dies on Mount Everest, it’s not like a typical emergency response. There are no rapid evacuation teams, no nearby hospitals, and often, no second chances. The death of a climber on Everest unfolds slowly, quietly, and painfully. And what happens afterward depends on where they died, how high they were, and what the family chooses next.

For some, Everest becomes their final resting place. For others, complex and costly recovery efforts follow. But no outcome is ever simple. Everybody left behind carries with it a story, a set of choices, and a ripple effect that touches climbers, families, Sherpa guides, and the mountain community.

Some Are Left in Place Out of Necessity

- In many cases, the body of a deceased climber cannot be moved due to extreme altitude, dangerous terrain, or lack of manpower.

- Frozen solid, often fused to the ice and rock, bodies are simply too heavy to carry down, especially in the death zone.

- Climbers who die on the route to the summit often remain exactly where they fell. Over time, their gear may fade, but their shape and presence remain as chilling markers.

These bodies become part of the landscape. “Green Boots” lies in a small limestone cave near the trail. Others are found near South Summit or Rainbow Valley, areas so high that even standing still is life-threatening. Sherpas and climbers often have to step over or pass by them—an emotionally jarring experience that lingers long after the expedition is over.

There’s also the psychological element. Seeing a lifeless climber just meters from the summit forces others to confront their mortality. Some turn back. Others push on, hoping not to meet the same fate.

Others Are Retrieved for Closure

- In rare but growing cases, families request the body be brought down, regardless of cost or risk. These operations can cost $30,000 to $100,000 or more.

- Sherpa-led recovery missions are challenging and dangerous. Teams may require weeks of preparation, oxygen supplies, specialized equipment, and medical backup.

- Most successful recoveries happen below Camp III (approx. 7,000 meters). Higher than that, retrieval becomes near-impossible.

Some bodies, such as that of Francys Arsentiev (“Sleeping Beauty”), have been moved from visible positions out of respect for the deceased and fellow climbers. Others, like American climber Scott Fischer, remain where they fell because recovery would be too dangerous.

These operations are not always successful. In 1984, a Nepalese recovery team lost their lives while trying to bring down a fallen climber. Since then, expedition leaders have been more cautious about accepting such missions.

Burial or Memorial Options

- Some climbers are cremated in Nepal, often following Buddhist or Hindu customs if the family agrees. Others are buried at lower altitudes in memorial cemeteries near Base Camp.

- In many cases, if the body is not retrieved, climbers are memorialized with plaques, chortens (Buddhist shrines), or cairns of stones along the trail.

- Families often return in later years to lay flowers or flags at these spots—turning the journey into a pilgrimage.

The Everest Memorial Park near Lobuche honors those who died trying to summit the mountain. You’ll find memorial stones dedicated to climbers like Rob Hall, Scott Fischer, and Shriya Shah-Klorfine. These silent spaces allow families and fellow mountaineers to reflect on the fragility of life and the price of ambition.

Not all climbers want to be brought back. Some leave written instructions asking to be left on the mountain, believing it’s the only fitting end to their life of adventure. For them, dying on Everest isn’t a tragedy—it’s a culmination.

Is It Time to Rethink the Ethics of Everest Expeditions?

Mount Everest has long symbolized human triumph and exploration. But as the number of climbers, deaths, and uncollected bodies grow, so do questions about the ethics of climbing the world’s highest peak. With hundreds of lives lost, including those of Sherpa guides who had no choice, is it time we take a closer look at the cost of these adventures?

The commercial success of Everest has come with an ethical price tag. What began as a pursuit of passion and courage is now sometimes criticized as a “pay-to-play” risk zone, where money, ego, and inexperience can be more dangerous than the mountain itself.

Should There Be Stricter Regulations?

- Every year, the Nepal government issues hundreds of permits to climbers, regardless of their previous high-altitude experience.

- Critics argue that many who attempt to summit Everest are unprepared physically and mentally for such a dangerous task.

- Some suggest tighter screening, mandatory training, or requiring climbers first to complete a peak above 6,000 meters.

The tragedy of Shriya Shah-Klorfine, a Canadian woman who died on her descent in 2012, reignited debate about permit regulations. She had limited mountaineering experience, yet made it to the summit—only to collapse on the way down. Her death highlighted how easy it is to underestimate the climb when it becomes accessible to anyone with enough money.

Governments and mountaineering associations are under pressure to reform permit policies, not to gatekeep adventure, but to ensure climbers understand the actual risks.

Sherpa Risk and Human Cost

- Behind every Everest expedition are Sherpa guides strong, skilled, and often under-credited for the success of others.

- Many Sherpas make multiple trips up and down the mountain in a single season, often carrying gear, fixing ropes, and leading climbers who may not even know how to use an ice axe properly.

- They face the same dangers but are paid only a fraction of what foreign climbers spend on the trip.

Sherpas have lost their lives retrieving bodies, fixing routes through the Khumbu Icefall, or guiding clients in storms. One of the most heartbreaking events was the 2014 avalanche, which killed 16 Sherpas in a single day. The accident highlighted the significant risks Sherpas face for the sake of the industry.

Many mountaineers now advocate for better pay, insurance, and decision-making power for Sherpa teams, because without them, Everest expeditions wouldn’t be possible.

Reclaiming the Sacredness of the Mountain

- For the local communities, Everest isn’t just a challenge—it’s sacred. Known as Sagarmatha in Nepal and Chomolungma in Tibet, it is worshipped as a goddess.

- Some see the growing number of climbers, waste, and deaths as a violation of the mountain’s sanctity.

- Some locals, monks, and cultural leaders have called for seasonal closures, rituals before climbs, and more environmental respect.

The sight of discarded oxygen tanks, frozen bodies, and overcrowded camps at high altitude is not just a climbing concern; it’s a moral one. The mountain is being treated like a trophy when, for centuries, it has been revered as a spiritual force.

Climbers now face the moral question: Are we honoring or exploiting the mountain?

Final Thoughts: The Mountain Remembers

Dead bodies on Mount Everest are not just remnants of tragedy. They are echoes of dreams that reached too high, of choices made in thin air, and of lives lost in pursuit of something greater than themselves.

Every climber who ventures into Everest’s death zone knows the risk. Some return as heroes. Others remain—forever part of the mountain.

Their stories remind us that while climbing Mount Everest may be one of the most incredible human feats, it also comes at a cost that not everyone can bear.

FAQs

1. How many dead bodies are on Mount Everest?

Over 300 people have died climbing Mount Everest. While some bodies have been recovered, many, especially those in the death zone, still remain on the mountain, frozen in place for decades.

2. Why are dead bodies left on Mount Everest?

Bodies are often left on Everest due to the extreme altitude, freezing temperatures, and the physical difficulty involved in retrieving them. Rescues can endanger more lives and cost thousands of dollars.

3. What is the “death zone” on Mount Everest?

The death zone refers to areas above 8,000 meters (26,247 feet), where oxygen levels are dangerously low. In this zone, the human body starts to shut down, making survival extremely difficult without oxygen support.

4. What happens to the bodies left on Everest?

Due to freezing temperatures and thin air, most bodies are naturally preserved. Some remain as they fell, while others become markers along the route, like the well-known “Green Boots” and “Sleeping Beauty.”

5. Is it legal to remove dead bodies from Everest?

There are no international laws preventing recovery, but it requires permission, high costs, and extreme effort. Some climbers’ families choose to leave them on the mountain as their final resting place.

6. Who was Green Boots on Mount Everest?

Green Boots is believed to be Tsewang Paljor, an Indian climber from the Indo-Tibetan Border Police who died in 1996. His body became a landmark for those scaling Mount Everest via the north route.

7. Have any dead bodies been recovered from Everest?

Yes, several bodies have been recovered, mostly from lower camps or when logistics allow. However, many bodies in high-risk areas like near the South Summit or Camp IV, remain untouched.

8. Are Sherpas involved in recovering bodies on Everest?

Yes, but it’s extremely risky. Sherpa guides are often the only ones capable of such missions, but they face serious danger. Many refuse retrieval tasks unless absolutely necessary due to past fatalities.

9. How much does it cost to bring a body down from Mount Everest?

The cost can range from $30,000 to over $70,000, depending on the location of the body and the resources required. Air support, Sherpa labor, and permits all contribute to the high expense.

10. Is climbing Mount Everest still safe despite these deaths?

Climbing Everest always carries risk, especially in the death zone. However, experienced climbers with proper training, preparation, and support can improve their chances. Still, even with modern gear, Everest remains one of the world’s most dangerous mountains.